By: Vasily Stokes

Editor-In-Chief

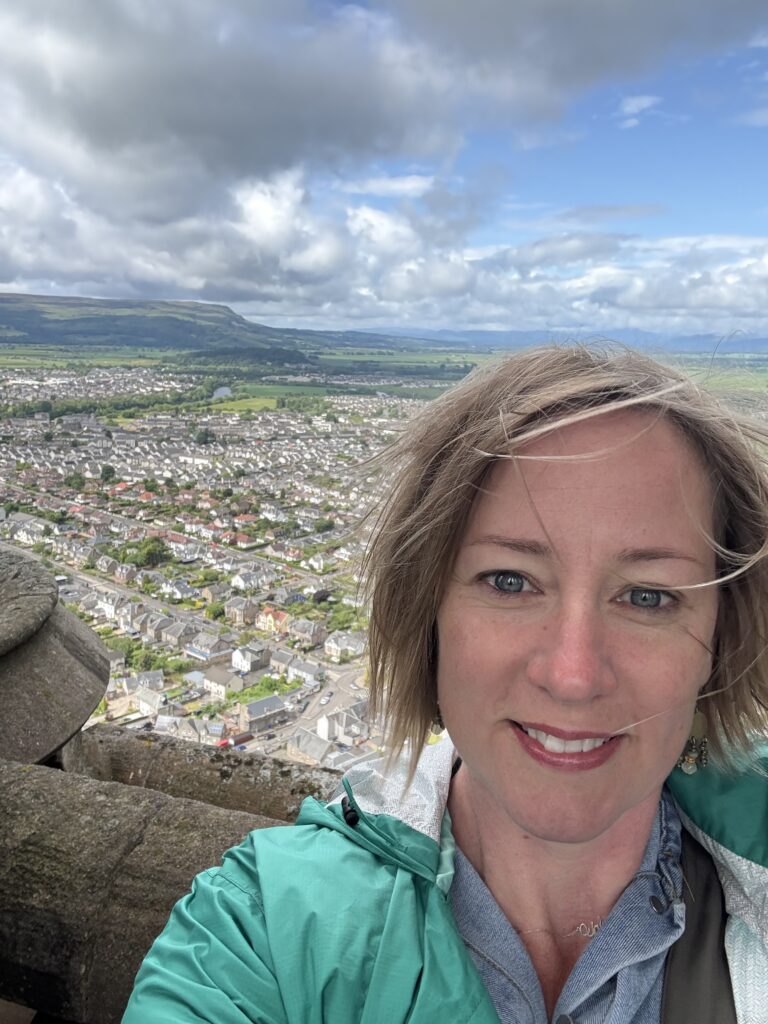

The History department utilized the art of film on September 11th as a teaching method, as the History department of Volunteer State Community College partnered with the local Palace Theatre of Gallatin to present the classic movie Braveheart. Braveheart is a film about the first Scottish war of independence, a tale of patriotism, bravery, and freedom. Professor Stella Pierce, Department Chair of the History, Economics, Geography, and Political Science departments of Vol State, is the Professor who added notes and used the film to teach about the historical context of Braveheart.

Braveheart is loosely based on the real-life First War of Scottish Independence, largely sparked by Scottish Knight William Wallace’s rebellion against King Edward I of England, also known as “Longshanks” and his son Edward II. The film is based on the 15th-century epic poem “The Wallace,” by Blind Henry, which inaccurately tells the story of William Wallace. The Poem and the movie itself contain major inaccuracies; however, the historical lesson that could be learned from this film still exists in a dramatic and fascinating manner.

After years of political crisis in Scotland, Edward I had conquered Scotland in 1296; however, in 1297, William Wallace from Southern Scotland had joined with Andrew Moray from Northern Scotland in open rebellion against English Rule. The first definitive act of rebellion on the side of William Wallace was the slaying of the English Sheriff of Lanark after the murder of Wallace’s wife by the Sheriff’s orders. Wallace and Moray fought under a pledge to John Balliol, the strongest contender for the Scottish throne, aside from Robert the Bruce.

The first official battle was the Battle of Sterling Bridge on September 11th, 1297. The same day as the showing of Braveheart at the Palace Theater, marking the 728th anniversary. Andrew Moray would be wounded in that battle and would die at an unknown time later that year. Even with the loss, the Scottish forces routed the English forces.

William Wallace and Andrew Moray were nominated as Guardians of Scotland. Wallace then proceeded with a campaign in Northern England, where 700 villages were set ablaze, stopping short of the city of York. Edward I then ordered a second invasion of Scotland, where his Army met with Wallace’s at Falkirk, although Wallace was able to put up a deadly fight against the English. Edward I’s army defeated William Wallace. Wallace was able to avoid being captured or killed during the Battle.

After the Battle of Wallace, the Guardianship of Scotland was surrendered to Robert the Bruce, the other contender for the Scottish throne; however, Wallace was then captured by Scottish Forces loyal to Edward. After a trial, Wallace pleaded that he could not be guilty of treason because he had never taken an oath of allegiance to England. Wallace was stripped naked, dragged through the streets of London by horse, and emasculated, disemboweled, beheaded, and quartered. Sir William Wallace of Scotland died on August 23, 1305. Wallace’s head would be placed upon London Bridge, and the rest of his limbs would be separated between the cities of Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Perth.

The next year, 1306, Robert the Bruce, although originally loyal to Edward I, would be inaugurated as King of Scotland in open defiance of the English War, rallying Scotland once again. Edward I, with his son Edward the 2nd, launched another invasion of Scotland, but was ultimately defeated by Robert the Bruce after a few decades of fighting, securing Scotland’s Freedom.

Professor Pierce primarily focused on what the movie got wrong and what it got right in the post-screening lecture. Here is a series of inaccuracies the film got wrong in its story. Wallace is portrayed as being a farmer before his father’s death, yet this is untrue. Wallace came from a low-level noble family that was not involved in farming. Wallace, in the movie, portrays himself as someone who does not fight for nobles but for the freedom of every Scot. Wallace fought for John Balliol, who was not featured in the film, but as mentioned, was one of the most likely to be chosen as king of the Scots. Braveheart was not William Wallace but was rather Robert the Bruce. Most of the costumes and face paint were inaccurate; for example, Cilts were not worn until several centuries in the future. There was no record of Prime Nocta (leaders bedding newlywed Women) being ordered by England. The Battle of Sterling Bridge, Wallace’s first battle in the movie, did not involve a bridge. The bridge, even though it was small, was the core part of the battle.

Inaccuracies related to the characters: Andrew Moray, the believed strategist of the duo, was not featured in the movie. Robert the Bruce was not a ‘traitor’ to Scotland, and there is very little to no evidence indicating that Wallace and Robert the Bruce ever met. Edward II was portrayed as cowardly through his homosexuality. This was a very homophobic portrayal, as Edward II has no evidence of being queer, and while he was not as imperialistic in his goals as his father, he was a great strategist who won a decent amount of battles in his time. William Wallace never met Edward II’s wife, who was a child at the time, so he did not have any romantic interactions with her.

Accuracies during the movie, he married his wife in secret, and she was killed by the English Sheriff. During the Battle of Falkirk, Wallace was abandoned by the Scottish nobles’ armies, who had pledged to fight at his side. His execution was very Brutal, in fact, even less Brutal than actually depicted.

What are the reasons for the inaccuracies? The direct sources that stem from these events are almost completely and neatly divided into those that are overly biased towards William Wallace and the Scottish Rebellions, and those that are overly biased towards Longshanks and the English forces.

The collaboration began when Professor James Hamilton suggested the idea as a creative solution to the legal limitations of showing movies on campus. The Palace Theatre welcomed the opportunity, seeing it as a chance to engage the public and bring the community together.

The department’s goal is to engage students in history in a new way while fostering connections with residents of Gallatin. “Movies are designed to entertain, but they can also teach and help fill in the gaps,” the department said. Professors hope that pairing films with guided discussion will encourage viewers to think more critically about the accuracy and meaning of historical films.

Professors will give a short welcome before each film and lead a 15- to 20-minute discussion afterward. The screenings provide a more relaxed and engaging experience than a typical classroom lecture. “The expectations are different, and so is the audience energy,” one professor explained.

Further screenings will include “Scream” on October 9th, Mel Gibson’s “The Patriot” on November 13th, Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X” on February 12th for Black History Month, “A League of Their Own” on March 12th for Women’s History Month, and “The Hunt for Red October” on April 9th. Possible future films include “Selma” and “Dr. Strangelove.” Faculty members most involved in the project include Professors Stella Pierce, James Hamilton, and Brady Duncan. Yet most of the praise should go to Professor Pierce for putting in most of the work to make this collaboration and unique learning experience happen. The History Department and the Palace Theatre hope to make this an annual tradition. “The director of the Palace has been unbelievably generous and patient,” the department said. “We’re hopeful this series will continue to grow.”

Be First to Comment